A Confluence of Waters

Exploring Connections with The Blue Marbles Project

In the Summer of 2019, we—Andi Wong and Margaret Warren—met for the first time at one of the Friday lunches at the Internet Archive headquarters on Funston Street in San Francisco. We met while planning art activities for the Decentralized Web Camp, and it was there that Andi first shared a blue marble with Margaret. But that is not where this story begins, and it’s certainly not where it will end.

This story is non-linear and organically expanding. Like mushrooms in a Fairy Circle. Like when websites used to have web rings. Like BuckyBalls: nano particles of carbon atoms in a spherical structure. Like the new vision of the web: decentralized and linked through nodes and edges. A synchronistic murmuration of inspirations and enchantment.

The ancient Greeks first declared the sphere the most perfect form and proclaimed it was the shape of the Earth and all the planets. Then on December 7, 1972, the crew of the Apollo 17 spacecraft made this vision evident when it produced this image of the earth, nicknamed “The Blue Marble,” on December 7, 1972.

Now jump to 2009, when a marine biologist, Dr. Wallace J. Nichols, known simply as “J” had an ambitious idea to hand his friend LeBaron Myers a blue marble. That simple act became an idea, which then became a movement. A low-tech-slow-motion global art project with a seemingly staggering goal of passing a blue marble through the hands of every (yes, every) person on OUR blue marble Earth, and along with each passing—a simple message of gratitude and reminder that everything we do on our water planet matters.

Dr. Nichols is an innovative and entrepreneurial scientist. In 1996, J placed a satellite-tag on an adult female loggerhead sea turtle that was released into the wild after being rescued in Baja, Mexico. Adelita, named after a local fisherman’s daughter, was the first animal tracked across the Pacific Ocean, traveling over 9,000 miles from Baja, Mexico to her place of birth in Sendai, Japan. Thanks to the internet, Adelita’s journey was followed by children everywhere.

Where is your water?

J often asks people the question: ‘Where is your water?’ to kick off a conversation. What is the special place where you find you go to the water’s edge? For some, it might be the neighborhood swimming pool. Others might answer that they go kayaking or sailing, or they think of a tropical island paradise where they go on vacation. Garden hoses, public fountains, an opened fire hydrant, or ocean surf… Really, there is no wrong answer.

Scientists and teachers spend a lot of time crafting thoughtful, open-ended questions when they want more than a simple “yes” or “no” answer.

In 2010, Andi went to hear J talk about sea turtles, after an introductory email exchange about water. She wrote to ask J about his view of the changing waters of the Gulf of Mexico, after seeing his CNN video report about the Deepwater Horizon oil spill online. When J asked Andi this question, she really had to think before answering.

Andi’s Water

My water begins in a small town in the California Delta called Locke, a historic rural Chinese-American community in the United States. The town of Locke was built in 1915 by Chinese residents, after the Chinatown in nearby Walnut Grove was destroyed by fire. I enjoyed lazy childhood summers in Locke, staying with my grandparents in their home on Main Street. My cousins and I had the run of the wooden plank walkways and the back alleys of this tiny four-block town. Locke was a place where we could roam and play until sundown, and we children grew up with very little knowledge of the extreme challenges faced by our families: The Page Act of 1875, The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, The Geary Act of 1892, The Alien Law of 1913 which prohibited the Chinese from owning land. There, in this isolated town, my mother’s family made it through the Great Depression and World War II.

In the 1940’s and 50’s, most young people—including my mother—left Locke, searching for greater opportunity and better living conditions. Today, in 2021, few residents of Chinese ancestry remain, and Locke has one of 300 failing systems in California that routinely supply roughly 1 million people with contaminated drinking water.

The river flows past my hometown of Sacramento, where I went to school, worked and got married, before moving to San Francisco. There the Bay waters swirl around Angel Island, where my grandmother, five months pregnant, landed on September 13, 1929, accompanied by my grandfather after a 31-day ocean crossing on the Tenyo Maru. Ye Ye, my grandfather, was free to depart, having taken up residency in California in 1911, as the son of a merchant, but Yin Yin, my grandmother, was held on the island for processing. The Angel Island Immigration Station transcripts document hours of intense interrogation. These records also revealed that Ye Ye was manager at United Meat Market for 36 firm members, and perhaps the cooperative’s pooling of investments explains how he was able to post the $1000 bail for Yin Yin’s temporary release eight days later. As ordered by the court, my grandmother returned to Angel Island carrying proof of childbirth: her 3-month old son Edmund—my father—and she was officially admitted to the United States as the wife of a domiciled Chinese merchant on March 17, 1930.

My water continues beyond Angel Island, flowing past the Golden Gate Bridge to San Francisco, where my two now-grown children built sandcastles on Ocean Beach and learned “you never turn your back on the Ocean.” It is a long oceanic journey from the farmlands of the Pearl River Delta of Southern Guangdong Province to reach “Gum Saan,” meaning “Gold Mountain,” what the Chinese called San Francisco, California. Much like Adelita the sea turtle, my immigrant ancestors needed both fortitude and good fortune to cross the Pacific Ocean.

For the past twenty years, I’ve worked in San Francisco public schools, as a teaching artist—a phrase coined to describe “an active artist who chooses to also develop the skills of teaching in order to activate a variety of learning experiences that are catalyzed by artistic engagement.” When the COVID-19 pandemic shuttered both schools and theaters, I focused on supporting two groups that struggled to adapt to the pandemic, often with limited access and experiences with technology: artists and elders.

Now I’m serving as project manager, researcher/archivist, and community liaison for a project called “Angel Island Insight,” with the Del Sol String Quartet and The Last Hoisan Poets. My work with poets Genny Lim, Flo Oy Wong, and Nellie Wong, also descendents of Angel Island immigrants, has filled me with a richer understanding and gratitude for the survival instinct and wisdom exhibited by the Chinese American diaspora. These vibrant elders taught me “haw meong suey,” an expression that literally means “Good Life’s Water” in Hoisan-wa, the dialect spoken by early Chinese immigrants. By writing new poems in Hoisan-wa, they are keeping the history and language of our ancestors alive and vibrant, in a time when intercultural understanding and cooperation are needed more than ever. Del Sol, unable to perform for audiences in concert venues, struggled with latency issues while streaming on Zoom. They pivoted to playing free outdoor pop-up concerts and commissioning composers to write new short musical works to inspire joy.

The history of the Chinese on Angel Island, America’s own immigration history, remains unknown to many. But when audiences board the ferry to Angel Island for performances by Del Sol in October, this artistic exploration of the history of immigration and exclusion will be presented with “haw meong suey,” a healing dose of ocean. For me, this was yet another surprising chapter in an epic voyage that began with the gift of a blue marble from Dr. Wallace J. Nichols at Gray Area Foundation for the Arts on July 29, 2010.

At that event, four large water coolers were lined up on a table, each filled with a colorful flotsam of plastic demonstrating the increasing levels of plastic pollution accumulating in our oceans from 1910, 1960, 2010, to 2030—an ominous depiction of the future, if no interventions were taken. Neat rows of stacked glass tumblers issued a silent dare to drink. Plastic Century was an experiential art installation created for World Oceans Day and the 100th anniversary of Jacques Cousteau’s birth. J and his project’s co-creators wished to convey the “feeling of strangeness, discovery, disgust, and delight… what we want to remain with people as they walk out into the great big plastic world.”

J was there to speak about his first-hand impressions of the Deep Water Horizon disaster, the largest marine oil spill in history. He had just returned from New Orleans after filming apocalyptic scenes of the ocean on fire from a helicopter. In Louisiana, he had walked on beaches littered with tar balls; filming and describing the details to his daughters. When I came across his report on CNN, I was sickened by his images of waters roiling in an oily sheen of sickly hues of yellows, reds, and white. “The Gulf,” he said, had become “the world’s largest petri dish.” with the unprecedented use of the chemical dispersant, COREXIT.

Noting that scientists are not often known for speaking about love, J spoke openly of his love for the ocean and his commitment to care for a world that his two daughters would grow to inherit. He discussed the value of using new tools and technologies to reach hearts and minds. Then, at the end of the evening, J gave each person in the room one blue marble. He explained the simple rules of the “blue game,” a ritual that has since become an integral part of my story, connecting me to thousands of others since that Summer in 2010.

Around the World with the Blue Marbles

I had just taken a new position at school: working in the computer lab. Excited to find ways that the arts might be integrated with technology, I soon discovered that all the kids really wanted to do in the lab was play a computer game called Marble Blast, where players roll a small marble through a variety of obstacles courses, without falling “Out of Bounds.” If you made it to the end, you were rewarded with a big burst of fireworks.

Image via Andi Wong

When I asked the kids why they liked playing the game, I learned that they knew that if they kept playing the game, they would improve. And one boy told me that he liked this game because he knew he could never die in it.

It was then that I decided what I would do with my class. We would play Marble Blast, away from the keyboard, in real-life.

When very young children draw their blue marbles close to their eyes while looking into the light, they will tell you that they see a whole menagerie of creatures, both real and imaginary — dolphins and whales, sea turtles and fish, merpeople and pirate ships. The children are eager to share what they see, and their eyes shine bright with wonder.

When I asked the children if it might be possible to pass a blue marble through the hands of everyone on Earth, they answered enthusiastically, “Yes!” The follow up question, “Can you do it by yourself?” made it clear that we would need to ask others for help.

At first, we only had one blue marble to play with. I asked the class, if they could send the Blue Marble anywhere on Earth, where would they like to see the marble go? After much discussion, the children decided that they wanted to see the Blue Marble at The World Series. We had to figure out a way. Incredibly, within minutes, we discovered Mr. Rogers, a fourth grade teacher, would help.

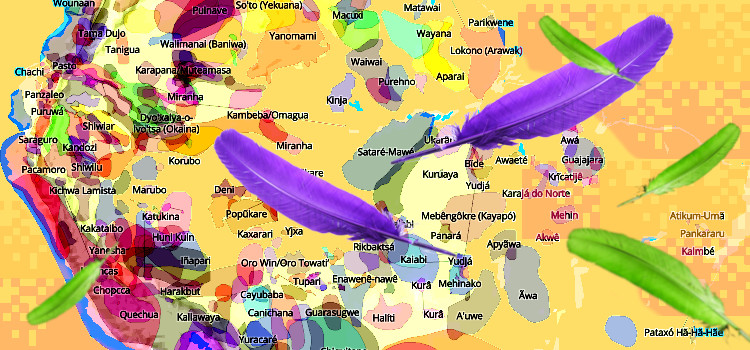

The next stop was Cuba, a place that was near impossible for most children to visit. The children’s imaginations caught fire. We bought a case of marbles and the game was on. Together, we traveled with Blue Marble to see the world beyond the United States. The Colosseum in Rome. The Berlin Wall. The Eiffel Tower. The Taj Mahal. The Great Wall of China! Family and friends helped the children to see the world by sharing their adventures through photographs and correspondence on Facebook.

It took three years, but the children finally achieved their goal to visit every continent on Earth, when a Blue Marble made it to Antarctica. Blue Marble followed the water, traveled across the Sahara Desert by camel, crossed the Alaskan frontier on the Iditarod, via gondola, rickshaw, airplane, and submarine.

Gif via Andi Wong

As the children learned about the Ocean and her importance to all life on Earth, they grew eager to apply their knowledge. They learned how to reduce, reuse, recycle, and ultimately refuse the plastic that soils their beaches by sewing their own cloth lunch bags. We sponsored a nest in the Yucatan Peninsula and celebrated the birth of sea turtle hatchlings. The third graders premiered Chelonia’s Story, an original opera about a young sea turtle and an ocean scientist who gently sings that captive turtles should be returned to the sea. On International Biodiversity Day 2016, the children used a new technology called Zoom, which was still relatively unknown then, to broadcast their sustainability fair celebration to a classmate in Saint Petersburg, Russia.

The project provided an opportunity for adults and children to learn together through play. When we made new connections between people and places, our planet felt a little smaller and nicer. There was a marble for everyone, so there was no worry about being left out. If a child lost a marble, we would ask what they might do differently and give them another to practice with. We all need to practice taking better care of our one Blue Marble. We are all in this together.

As time passed, the photo album of Blue Marble images grew, but with each school year, we also became more and more aware of the accelerating speed of environmental change. Would our photos eventually become a record of places transformed beyond recognition? Would the stories and information attached to the images be useful in the future? Social media platforms were being used to manipulate public opinion and spread disinformation, and I was looking for another way to work with my images. That’s when I met Margaret.

As if we were guided by two rivers headed towards a confluence, we met in 2019 when I was invited to support artistic projects at the first DWeb Camp at the Mushroom Farm.

This is when I first learned of Margaret and her project: ImageSnippets. It was then that I asked her the question: “Where is YOUR water?”

Margaret’s Water

When I was a very little girl, my father would play marbles with me, but not in the traditional way with shooters and circles. Instead, we would take a big thick quilt, spread it out in a haphazard way and give it hills and valleys. Then we would take the marbles and move them around the quilted landscape. Maybe to my dad they were like little ‘troops,’ but I wanted to organize and study them. I grouped them by colors and types; categorized and counted. Later on, when our family would go flea market shopping, I so loved the marbles, it gave me my own little thing to seek out and collect while my parents collected cameras or other gadgets they were passionate about.

Over the years, I have created many projects and professions, but most often I say I am an artist, a creator, a researcher, and a technologist—even though I feel like these labels keep overlapping and meandering. Looking back, I can now see I’ve spent most of my life responding to an inner curiosity for things like making art and photographs, describing images, discovering synchronicities, and building networks of people and machinery. Rolling and tumbling from one eddy to another, my life itself has felt both fluid and yet also deliberately and persistently guided by a much deeper current.

My water begins in the very far western tip of Kentucky, where I was born within ten miles of the Mississippi River. I was born in the county seat in a little town called Clinton, not far from an even smaller town called Columbus, which sits on a bluff overlooking the river. In the 1800’s, Columbus was much larger; a busy port for trains, barges, steamboats and all kind of river traffic on North-South trade routes. From Chicago, Illinois to Mobile, Alabama to New Orleans, Louisiana, ferries moved travelers across the nearly mile-wide Mississippi as they journeyed westward seeking fame, fortune, and new opportunities.

Some of my ancestors started out to be some of those westward seekers, but they just didn’t make it past the river. In fact, one story told in my family is that they decided to settle in Kentucky because one of my great-great-great grandmothers had taken one look at the river and said, “I’m not crossing that!”

As a young child, my story continued south to the Gulf of Mexico when my parents moved to Northwest Florida, to an area called the Big Bend.

The waters of this part of Florida are quite special. This area is home to both the largest diveable underwater cave formation in the world (Wakulla Springs) and also to one of the oldest National wildlife refuges in the United States. Established in 1931, the coastal area of St. Mark’s was founded as a protection for migratory birds. The wetlands and estuaries of this area are also referred to as the ‘Forgotten Coast’ or ‘the Other Florida,’ because this area is so different from the white sandy beaches, palm trees, and condos that most people think of when they think of the state. The refuge protects longleaf pine savannas and coastal marshes as far as the eye can see. Made up of salt waters from the gulf and freshwater from nearby springs and rivers, this ecoregion is known as the southern coastal plain and is home to an amazing array of flora and fauna.

Unlike the fishermen and other inhabitants of these coastal towns, my parents were young artists interested in astronomy, nature, and wildlife. We regularly went canoeing and hiking in the area. Through my father’s work as a photojournalist, we circulated around the coast learning about the people and the environment. My father would often pull me out of school to bring me along on his feature photography days to take photos of places like St. Mark’s for the Tallahassee Democrat, the local newspaper.

As a teenager, my waters moved me in a new way, into a tour of duty in the US Coast Guard.

When I was part of the Coast Guard, I always felt so proud to be part of a mission for search and rescue, tending to buoys, and coordinating environmental cleanup in all of the waters of the US. Though I served only one term in the Coast Guard as a Cryptographic Electronics Technician, I did travel to the Great Lakes, the New York City Harbor, the SF Bay Area in California, Kodiak, Alaska, and then back again to the Mississippi River in New Orleans.

Electronics study in the Coast Guard led to computer science in college, and then various jobs that circulated around photography, technology, music and the arts and from the Gulf Coast to California and back again multiple times. Following my curiosity over the years, I was inspired to explore a unique problem: how to describe images with more formalized, machine-readable techniques.

Being raised by artists, naturalists and photographers had undoubtedly inspired me; but I had also been the seven year old making encyclopedias of bird pictures matched to their scientific names. I made all of my school writing projects about images. When I would print my own photographs in the darkroom with my father, I always made sure I had written all of the ‘metadata’ (the who, what, why, where, how, when) on the back of the print:

As my technology career evolved with the web, I strived to find the best ways to publish my images online with their metadata. But to my dismay, the web was actually evolving in such a way as to de-value publishing and curation methods that would have handled image metadata more appropriately.

In fact, to this day, many content producers continue to exercise poor metadata habits with images, and these habits—whether learned or ignored—have actually led to much more severe problems as a result. The serious problems associated with misinformation and disinformation on the web are now widely recognized and widespread. In particular, images stripped of their original metadata have been re-contextualized to manipulate emotion and used to polarize viewpoints.

Yet it can be challenging to write metadata. Many people just don’t want to write it, as they often don’t want to take the time to add context and intention to images, and don’t think about what will happen to the metadata once an image gets on the web. The technology behind centralized social media photo sharing has deliberately made it difficult to keep metadata attached to images, while at the same time retaining your image collections to keep you further tied to a platform.

We are still a very long way from mastering what it would mean to be able to formally record the context around the making of an image, as well as the intention with which that image is being shared. Though computer vision can produce some interesting demonstrations of image classification, language is very ambiguous and subjective, and artificial intelligence is a long way off from capturing the subtleties of image metadata.

In general, it can be said that sharing images properly on the web requires a human-centered thoughtfulness—a theory not embraced by advertising revenues.

ImageSnippets

Thus I started building ImageSnippets. ImageSnippets is a web based system that has now been in development for over 11 years with ideas stretching back almost 20.

I call ImageSnippets a metadata management system, but it’s designed to be so much more. It can be used to curate image collections, and be an interface for images to be linked in interoperable ways to other data on the web using linked data. It’s also being used as part of research projects for modeling formalized image descriptions, with descriptions by subject matter experts. All of this can be done in such a way that the descriptions can be machine-readable, and thus assembled into image-based knowledge graphs—also known as image graphs—in the process. In this way, ImageSnippets is also a research tool for knowledge representation.

Instead of requiring images to be held in centralized data stores, the tool is designed to sit as a layer over the images. That means the data can be held anywhere on any server, and the data is openly available and queryable using the SPARQL query language.

At the 2019 DWeb Camp, I worked as a volunteer to build out the local mesh network, as well as to design a collaborative art project. When I met Andi through this work and showed ImageSnippets to her, she immediately embraced the vision of ImageSnippets. Extending the idea of network nodes to the blue marbles, we both excitedly saw how it could be used to connect the stories of the photographs collected between all those people she and her students gifted with blue marbles.

Publishing these images here on COMPOST with Distributed Press, we are fortunate to see this experiment come alive. But we are just at the beginning of this next phase of our story. This article represents a next step in taking image and metadata publishing techniques to decentralized protocols.

Computer scientist Admiral Grace Hopper said, “If you do something once, people will call it an accident. If you do it twice, they call it a coincidence. But do it a third time and you’ve just proven a natural law!” When a blue marble is passed it is a gift of gratitude for the good work that you do. When we share our gratitude in this way, we are building understanding, empathy, and love in our interconnected world. The blue marble opens up pathways through which we can learn and understand one another through a shared connection with our waters.

Image via Andi Wong and Margaret Warren

The images in this piece flip to reveal their metadata and the images themselves also contain the embedded metadata. This functionality is provided by ImageSnippets, a project by Margaret Warren. Image metadata allows others to understand the context and provenance of images when they are shared and published.

The authors wish to thank COMPOST for helping us to find confluence through our parallel exploration of the wild, domestic, and virtual waters that have shaped us as individuals. Andi & Margaret will continue to reveal, preserve, and share digital stories with The Blue Marbles Project, joining The Blue Mind Network’s global efforts to put #bluemind science into action to create common knowledge and practice.

If you would like to join their project, please visit bluemarble.pics to float a note to Andi at ArtsEd4All and dive into metadata with Margaret at ImageSnippets.

Artist/educator Andi Wong enjoys connecting dots and coloring outside the lines. She is project coordinator for ArtsEd4All.

Artist/technologist Margaret Warren collects synchronicities and tells stories with metadata. She is the creator of ImageSnippets.

We built this little tool for you to inoculate other web spaces with the ideas and stories contained in this issue. To re-publish this piece under the terms of the license, click below to copy the markdown.